On his parents’ immigration story…

My parents immigrated to the US from Mexico. They arrived as migrant field workers — and for the first 6 years of my life, we would follow the fruit harvest from Mexico, through southern California, to Northern Washington State and back to Mexico — every year.

My family was part of the seasonal workforce. In April we would leave Juchitlan and arrive in Oxnard, California where my father picked lemons and strawberries until June. Then we would move to the central valley of California (From Modesto to Gridley — depending on the year), where my parents would pick peaches, nectarines, walnuts and then in September/October we would move to Oroville Washington to pick apples. Sometimes we would move back to the central valley for a few weeks and then back to Oroville for the end of the harvest. But by early December, we were always back in Juchitlan Mexico.

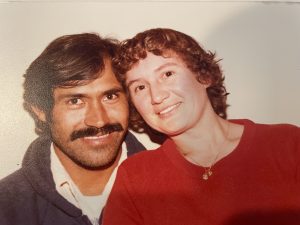

Lepe’s father picking apples in Washington.

This was the case except for my first Apple picking season. 9 months after being born, my parents were getting ready to move to Washington, but they were unable to organize childcare — so an aunt flew up from Mexico and took me back to Juchitlan. My mom was visibly distraught by my absence, and the owner of the apple orchard told her that the following year, she should bring me and if needed, she would take care of me while they worked.

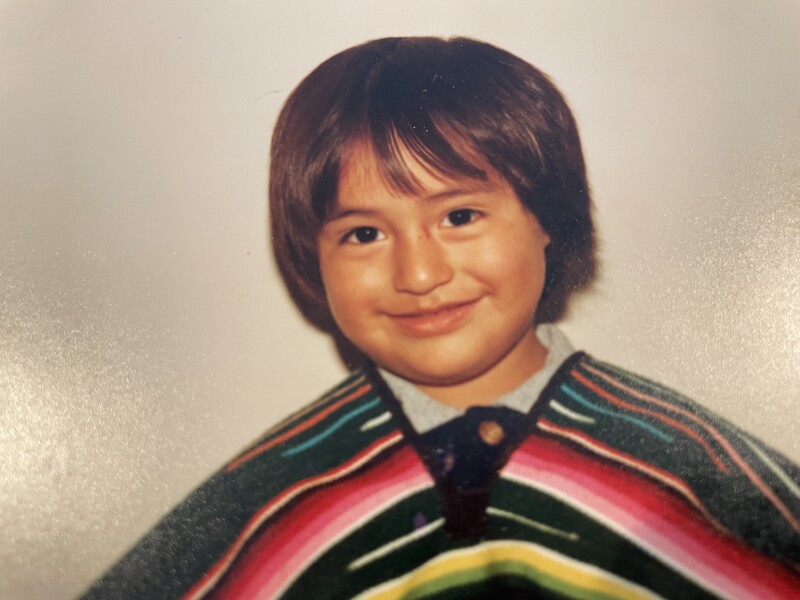

Taken from “Foundation: Birria and Tacos are my Comfort Food.”